At the 2024 Puentes summit, Claire Selinger and Minou Arévalo Ramírez discuss their cross-border collaboration on mental health care training for communities in Central Texas and Puebla, Mexico.

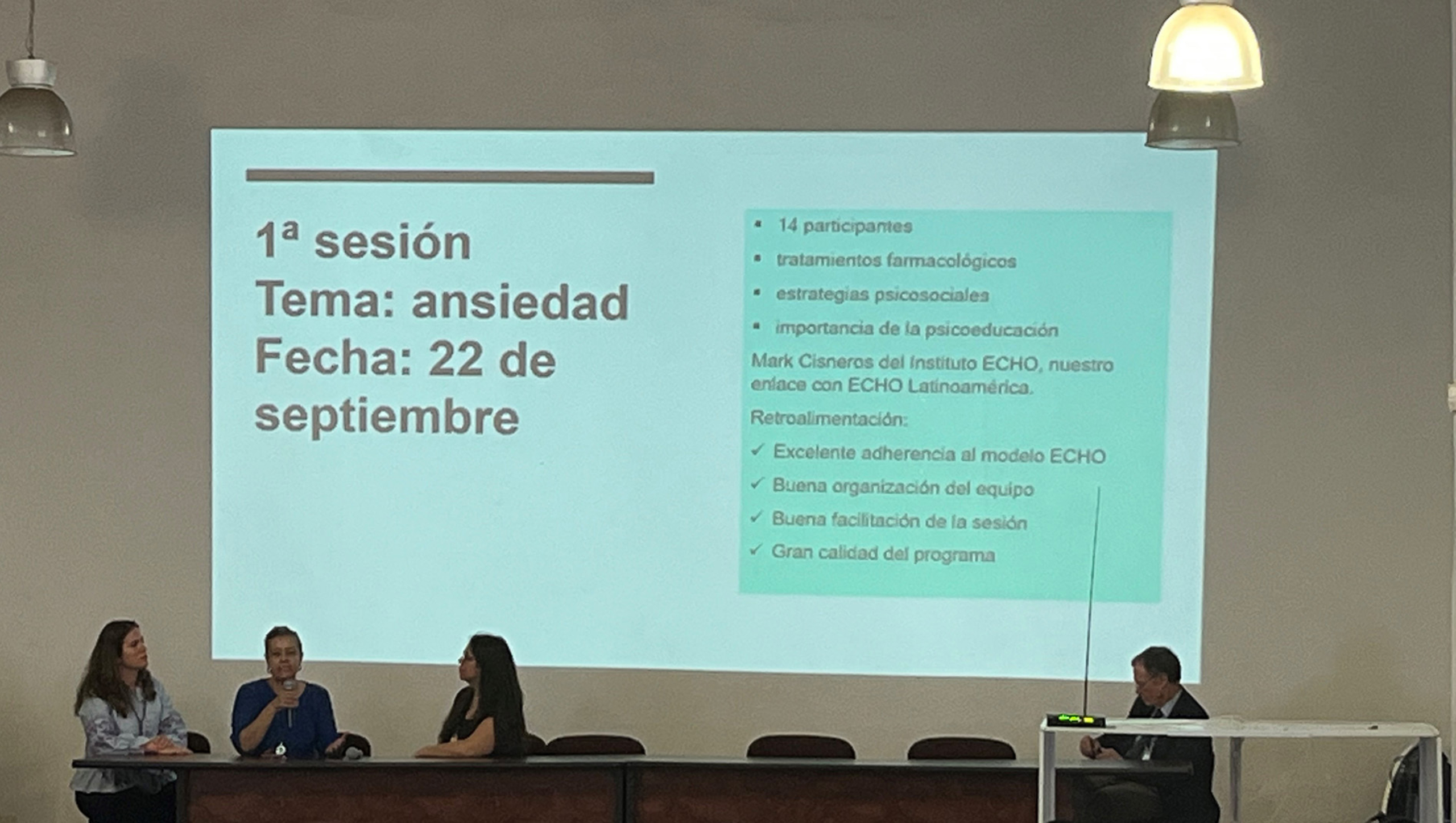

Left to right: Psychiatrists Claire Selinger of Dell Med and Minou Arévalo Ramírez of Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla — representing the mental health education working group — and ECHO facilitator Kristin Escamilla, Dell Med psychiatry faculty.

As new friends, Claire Selinger of Dell Medical School’s Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and Minou del Cármen Arévalo Ramírez of the Facultad de Medicina at the Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla (BUAP) call themselves “Tex-Mex.” They’ve shared laughs, dinner outings in their respective home cities and introductions to each other’s daughters. As colleagues, they share a cross-border partnership in global mental health spanning Central Texas, the U.S. and the state of Puebla, Mexico. They are each one end of a new bridge: Project ECHO, a joint effort that equips mental health care providers with additional training and strives to improve outcomes for the medically underserved in both countries.

Created in 2003 by Sanjeev Arora of the University of New Mexico, Project ECHO is an interactive training and peer support model for building collective understanding. It features facilitated virtual gatherings in which health expert participants distill evidence-based best practices on a clinical topic and then “echo” them: first through a group discussion of cases and second by applying their learning outward, benefiting patients in communities and professional peers via generative learning. ECHO — originally the Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes — has now been applied successfully worldwide in areas beyond health, including education, public service and media.

In Puebla, Mexico, on the eve of the fourth Puentes summit in October — an annual initiative hosted by Dell Med’s Division of Global Health and the BUAP Facultad de Medicina as part of the overarching AMPATH/MAPAS México partnership — Claire and Minou looked back and ahead on Project ECHO’s work and impact.

Q&A

Share a bit about your background. How and when did your work together begin?

Minou Arévalo Ramírez (MAR, in Spanish): Currently, I’m a clinical psychiatrist and the academic coordinator for psychiatry at BUAP Facultad de Medicina. I have a master’s in medical sciences and a doctorate in institutional direction, and I currently give classes to pre-graduate students in the medical school and to students doing a psychiatry specialty. They rotate with me in the psychiatry academy.

Claire Selinger (CS, in English): I’m an assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Dell Med, the director of undergraduate medical education for psychiatry, the psychiatry clerkship director and a child psychiatrist. I have clinic in the community: school-based mental health.

MAR: It’s really been a short time that we’ve known each other. We started to work without meeting each other in person, only on Zoom. However, we’ve done a great job!

CS: It’s really nice to be together in person; it makes a big difference. We met via Zoom after last year’s Puentes summit. Then, the mental health working groups identified that communities were all lacking in mental health care. There were three areas of dire need: alcohol abuse, PTSD and depression.

My idea was to teach physicians or practitioners how to be more comfortable treating those conditions. And the model of Project ECHO worked really well in central Texas; I had been a part of Project ECHO for child mental health. I thought, well, it’d be really nice if I had someone who wanted to do that with me. I asked Laura Indira Gomez (director of postgraduate research at BUAP psychiatric hospital), and she said, “I’m too busy, but my friend Minou is just like you. Let me introduce you!”

What are the features of the Project Echo telementoring model? How have you adapted it to meet the mental health needs of Central Texas and Puebla?

CS: It’s not a traditional lecture. It’s ten slides of the things you absolutely need to know about treating this condition followed by case discussions with lots of time for questions and answers. We have six modules — depression, anxiety, PTSD, alcohol abuse, perinatal depression and insomnia — and we’re running the same curriculum in Central Texas and in Puebla this fall. Minou’s already started, and we start later on.

Each hour is a different topic, spread over six to 12 weeks. The participants are prescribers: pasantes (BUAP’s social service year medical students), doctors and nurse practitioners. They’re getting expert-level advice about how to care for patients who they might find have tricky circumstances. Our Austin facilitators are from the school of medicine, but Minou’s are actually private practice folks and people from the hospitals.

The mental health education working group delivering a presentation at the 2023 Puentes summit.

MAR: In the first ten minutes, an expert gives key points of the theme. Afterward, doctors present the brief clinical cases. If there are doubts, you ask questions, always guarding patient confidentiality, of course. The one who presents the case poses a specific question, such as, “For this patient, how can I help them further?” “Is what I’m doing correct?” It’s very dynamic. The doctors who are participating, though they may not be experts in a theme, can give comments or suggestions about how they have managed their patients. And the objective is that the expert — in this case, the psychiatrist — grounds these ideas. All participants who have had similar cases can express their doubts or can suggest what for them has been best in the treatment of their patients. And with the expert, they now land on what is most appropriate.

What kind of impact are you aiming for with the trainings in Austin and Puebla? And how’s it all going so far?

CS: When we initially conceptualized it in Puebla, we thought it would be primary care providers in Atlixco and San Francisco Xochiteopan, but then we talked with Becca Cook and Minou about the pasantes. They were easier to connect. They’re out there in rural places alone, and they are really hungry for this type of information. We thought that would be an easier cohort to start with.

In Central Texas, we could do residents; that’s the equivalent of a pasante. Residents who are struggling in their clinic with a lot of mental health care, like internal medicine or family practice residents, would be an example. Faculty members have said it would be helpful.

Pasantes and other clinicians from BUAP’s medical school deliver a health presentation to children at a rural primary school in San Francisco Xochiteopan, Puebla.

MAR: The first Puebla training went really well! We had the first two modules — depression and anxiety — with one on insomnia to follow. The first had 14 doctors, and in the second there were 19 doctors. An ECHO coordinator was there for the first one and gave us feedback. He said that we’d understood the ECHO concept well and congratulated us.

CS: We had 12 prescribers enrolled, and we hope to enroll 20 to 30. The nice thing about ECHO is that if you think about 20 to 30 prescribers seeing 50 to 100 patients a week, you can see how you’re spreading knowledge exponentially. It multiplies. But we want to keep the groups small enough that people feel like they can ask questions.

This is Claire’s third visit to Puebla, and Minou visited Austin for the first time in September. As clinicians and researchers, what have you learned about the mental health needs of the other’s home state?

MAR: That they have the same needs! It’s what I always tell my students: Although it may be a community that speaks to different cultural conditions, in the end the problems are the same.

CS: I completely agree. We struggle with the same issues on both sides of the border in many ways. It was very eye opening, seeing an inpatient psychiatric hospital in Mexico. Parts of it reminded me of my training at Veterans Affairs. The patients were outside a lot, which I loved to see. They don’t have a child inpatient unit in Puebla; the children have to go to Mexico City. Getting to know Mexican health care and culture better has been helpful in my clinics in Texas.

I take care of a lot of patients whose families come from Mexico, particularly in my school-based care clinics for Integral Care. They’re always delighted to hear about my relationship with Puebla and my commitment to helping Mexico as well as to not to have to use a translator and just speak with me directly. I think it helps build their confidence in me as their child’s provider.

Tell us about being part of building the broader AMPATH/MAPAS México partnership. What successes and challenges have you encountered in working on an international team?

CS: I think the AMPATH México Bilateral Innovation Award really helped us to trust each other and to become partners. Without the grant, we couldn’t have had that April trip. Minou coming to Austin was really helpful as was the Hogg Foundation grant and getting Marta Horta Granados on board, a Project ECHO coordinator and social work graduate student at UT.

MAR: Something that I’ve really enjoyed about working with Claire is that I speak imperfect English, and she speaks imperfect Spanish, but we’ve understood each other really well! We’ve had really good communication, and we’ve been able to work and advance the project promptly. The doctors who are participating are pleased with this. While we don’t move ourselves into the communities, we are still helping the people there through their doctors.

Participants of the 2023 Puentes summit gather with AMPATH México leadership in Puebla, Mexico.

MAR: At Puentes this year, we’re going to present these advances and ask how we are going to publish the work and share it further. This is basically what we have to work on now.

CS: We’re really good at doing things, but we’re not really good at publishing the things that we’re doing. I think we have a lot of lessons we can share now. We’re doing something in two countries, and it’s helped our practice to work together.

What is the next step for our relationship continuing, and how is that feasible with other demands on our time? Do we want to keep the modules going, or if we’re going to do new modules, do we bring in new people? We want to get our resident and student exchanges going. We want to support Minou in her work teaching and inspiring the next generation of psychiatrists. She should not have to be the only psychiatrist at BUAP — we want to be there with her. We’d like to hear what other people think should be the next steps too.