Alia Pederson, rising second-year medical student at Dell Medical School at The University of Texas at Austin, describes herself as highly motivated by curiosity.

But with every topic she’s tackled throughout her education — Russian language and culture, neuroscience research, and now, medicine — cultivating relationships and community has been the driving force behind her work.

And Pederson, raised in Austin, learned more than just biology this year: Through elective courses offered as part of Dell Med’s Leading EDGE curriculum, she witnessed glimpses of humanity and healing that will stay with her for years to come.

Alia Pederson, Class of 2026.

You just completed your first year of med school. What newfound knowledge are you walking away with?

This spring I took two powerful electives: The first was called the Healer’s Art, which is taught by the palliative care faculty. We talked a lot about the difference between treating and healing, and how to nurture oneself as a healer in order to offer that healing perspective to one’s patients. We had sessions on grief and sessions on what we or our patients perceive to be miracles. It connected me with mentors and with my classmates in unexpected, emotionally meaningful ways.

The other elective I took was with the Texas Center for Pediatric and Congenital Heart Disease. That elective is unique because it gives first-year medical students unparalleled access to highly specialized surgery. Our culture has so much mythology around the heart. Even though we understand that most of our experience comes from the brain, the heart still often defines the boundary between life and death.

Congenital heart surgery takes children over that boundary — the heart stops while patients are on a heart-lung machine during the operation — and then brings them back, stronger, with a better chance at a “normal life.” Watching the newly repaired, healthily beating heart of a child, standing with the team as they closed that child’s chest, giving that child the best chance for this procedure to become a distant memory — and having that be my first experience with surgery? What a gift.

How are you already seeing your classroom lessons translate to practice?

The combination of these two very special electives was important to me for just that reason. The most meaningful experience I had this year started with an early morning text message on a weekend that said, “Today’s transplant day. We’re doing a procurement. Do you want to come?”

From that moment, there’s almost no time to reflect — you just go. Yet, I wept for that child and their family. The donor was not even a toddler. I reached out to the mentor that I had in the Healer’s Art elective and said, “I have this opportunity. It could be a once-in-a-lifetime thing; I don’t know if I’m going to be a cardiothoracic surgeon. But I want to honor this child and honor my grief now so that I can focus on being present during the surgery.” He wrote back very quickly with some great advice for holding that space in an authentic way.

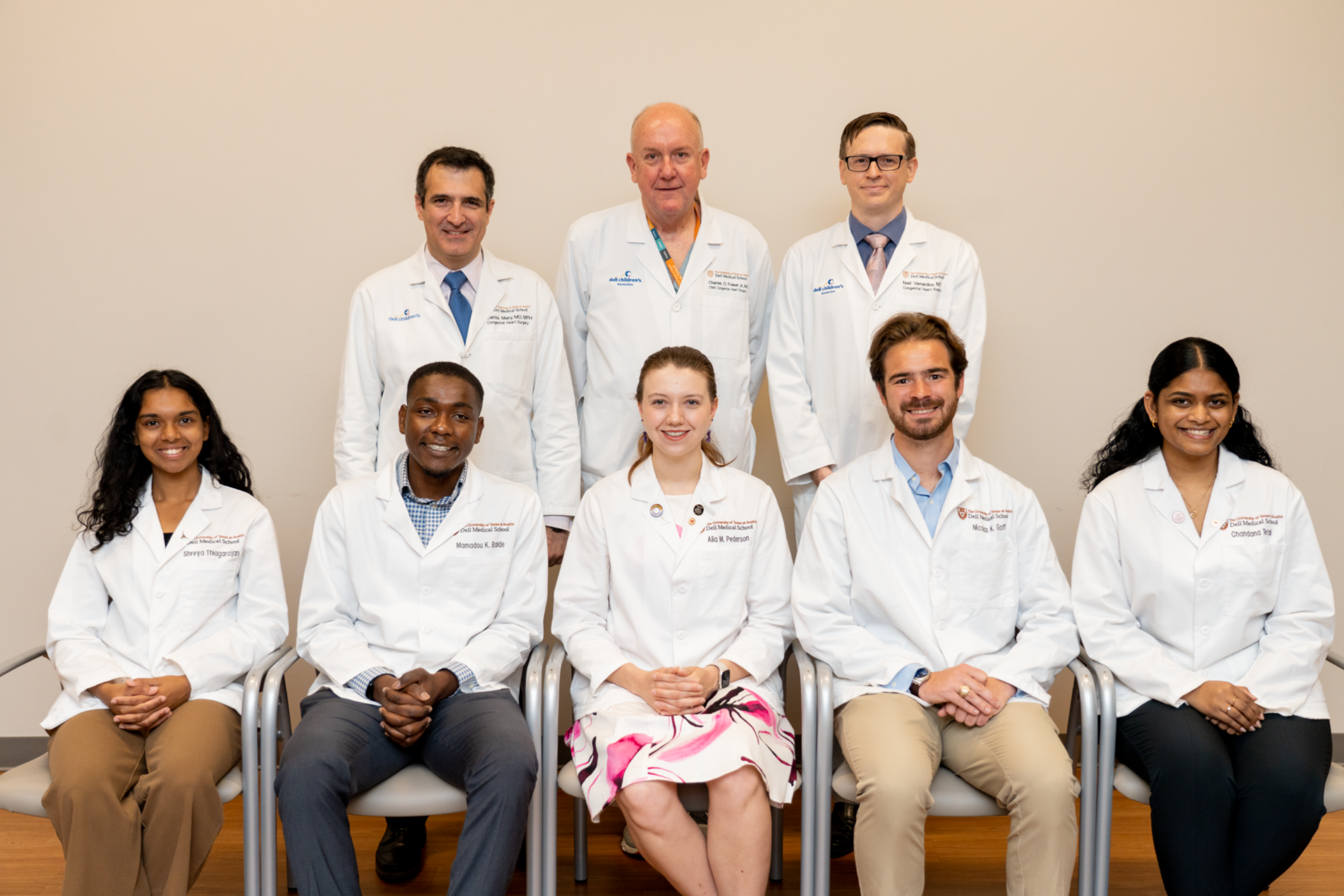

Pederson’s cohort and faculty mentors in Dell Med’s pediatric congenital heart surgery elective. Back row, left to right: Carlos Mery, M.D., Charles Fraser, M.D., and Neil Vernardos, M.D. Front row, left to right: Shreya Thiagarajan, Mamadou (Korse) Balde, Alia Pederson, Nico Goff and Chandana Tetali.

It was still hard. I was grieving for this family and this child that I didn’t know, and I was simultaneously imagining what it could possibly be like if my own young daughter was on that table. I don’t have the life experience or the surgical experience to keep myself from making that connection right now. I needed to do something extra to process that if I was going to be the member of the surgical team that they needed me to be. I am so grateful that Tyler Jorgensen, a doctor training in palliative care at Dell Med, was able help me do that.

The procurement itself, removing the heart from the donating child, is an incredible example of interprofessional collaboration. Physicians, surgical physician assistants, nurses, perfusionists, logistics coordinators, pilots and ambulance drivers, the organ procurement organization representatives and so many others are critical to the transplant’s success. The heart can only be out of a human body for four hours, and the donor could be anywhere in the country. There are two totally separate teams, one for each child. Constant communication is a must.

I was able to be at both the procurement and the transplant. During the transplant, I watched the screen of the surgeon’s camera as he placed the heart into the receiving child’s chest. It isn’t like in the movies, where you sew in the heart and then you put paddles on and start it again. The heart actually starts to beat on its own. I can’t describe how beautiful that is. You see the heart of this child who has died, now ferociously determined to live again.

I remember the anesthesiologist going, “Wow, it’s really ready.” And it was — it came back fast and with perfect rhythm, giving this baby (who had been on the transplant list since before they were born) new life. I wish the donor child’s family could have seen that. I think it would have provided a lot of closure to see just how strong their baby’s heart still was and how it’s going to continue on.

What’s on your mind as you consider your future career?

I recently read an article titled “Leaders Stay, Others Run.” It’s about physicians in Sudan who are currently choosing to stay amid the new civil war; some have lost their lives and others are subject to threats or torture. And yet they continue to stay because people need health care.

Staying in Austin is very different from staying in Sudan. But the article reminded me of my personal responsibility to care for our community, despite the increasingly challenging intersections of law, poverty and health care seen here. I’m part of a lesbian family, and I have a daughter, and I am concerned about the ways that changing laws here might affect us or her. I am afraid of what they will mean for my future patients and how to handle the moral injury that comes from being potentially unable to provide medically necessary care. I have a great responsibility to my family. I also have a great responsibility to my community, especially going to Dell Med with our mandate to improve health care locally.

We have an opportunity to build something for people who are moving to Austin. More importantly, we have an opportunity to expand health care access for Austinites who have gone too long without it. Our family hopes to stay and invest in this community for the long haul.